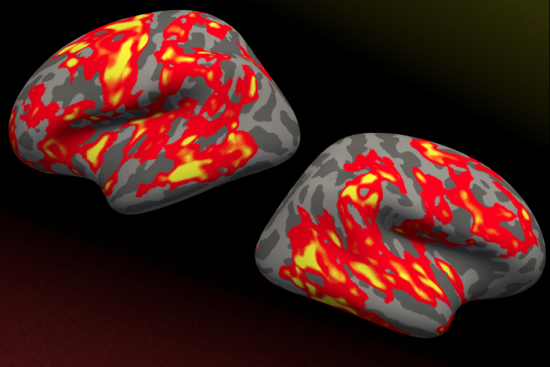

Brain regions that grew significantly thicker in reading-disabled children whose reading improved after an intensive summer treatment program, as shown in the red and yellow areas. Neither a control group nor children who did not respond to treatment exhibited changes in brain structure.” Image: Rachel Romeo

Dyslexic children from lower-income families benefit more from summer reading intervention.

About 20 percent of children in the United States have difficulty learning to read, and educators have devised a variety of interventions to try to help them. Not every program helps every student, however, in part because the origins of their struggles are not identical.

MIT neuroscientist John Gabrieli is trying to identify factors that may help to predict individual children’s responses to different types of reading interventions. As part of that effort, he recently found that children from lower-income families responded much better to a summer reading program than children from a higher socioeconomic background.

Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the research team also found anatomical changes in the brains of children whose reading abilities improved — in particular, a thickening of the cortex in parts of the brain known to be involved in reading.

“If you just left these children [with reading difficulties] alone on the developmental path they’re on, they would have terrible troubles reading in school. We’re taking them on a neuroanatomical detour that seems to go with real gains in reading ability,” says Gabrieli, the Grover M. Hermann Professor in Health Sciences and Technology, a professor of brain and cognitive sciences, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, core member of the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, and the senior author of the study.

Rachel Romeo, a graduate student in the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology, and Joanna Christodoulou, an assistant professor of communication sciences and disorders at the Massachusetts General Hospital Institute of Health Professions, are the lead authors of the paper, which appears in the XX issue of the journal Cerebral Cortex.

Predicting improvement

In hopes of identifying factors that influence children’s responses to reading interventions, the MIT team set up two summer schools based on a program known as Lindamood-Bell. The researchers recruited students from a wide income range, although socioeconomic status was not the original focus of their study.

The Lindamood-Bell program focuses on helping students develop the sensory and cognitive processing necessary for reading, such as thinking about words as units of sound and translating printed letters into word meanings.

Children participating in the study, who ranged from 6 to 9 years old, spent four hours a day, five days a week in the program, for six weeks. Before and after the program, their brains were scanned with MRI and they were given some commonly used tests of reading proficiency.

In tests taken before the program started, children from higher and lower socioeconomic (SES) backgrounds fared equally poorly in most areas, with one exception. Children from higher SES backgrounds had higher vocabulary scores, which has also been seen in studies comparing nondyslexic readers from different SES backgrounds.

“There’s a strong trend in these studies that higher SES families tend to talk more with their kids and also use more complex and diverse language. That tends to be where the vocabulary correlation comes from,” Romeo says.

The researchers also found differences in brain anatomy before the reading program started. Children from higher socioeconomic backgrounds had thicker cortex in a part of the brain known as Broca’s area, which is necessary for language production and comprehension. The researchers also found that these differences could account for the differences in vocabulary levels between the two groups.

Based on a limited number of previous studies, the researchers hypothesized that the reading program would have more of an impact on the students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. But in fact, they found the opposite. About half of the students improved their scores, while the other half worsened or stayed the same. When analyzing the data for possible explanations, family income level was the one factor that proved significant.

“Socioeconomic status just showed up as the piece that was most predictive of treatment response,” Romeo says.

The same children whose reading scores improved also displayed changes in their brain anatomy. Specifically, the researchers found that they had a thickening of the cortex in a part of the brain known as the temporal occipital region, which comprises a large network of structures involved in reading.

“Mix of causes”

The researchers believe that their results may have been different than previous studies of reading intervention in low SES students because their program was run during the summer, rather than during the school year.

“Summer is when socioeconomic status takes its biggest toll. Low SES kids typically have less academic content in their summer activities compared to high SES, and that results in a slump in their skills,” Romeo says. “This may have been particularly beneficial for them because it may have been out of the realm of their typical summer.”

The researchers also hypothesize that reading difficulties may arise in slightly different ways among children of different SES backgrounds.

“There could be a different mix of causes,” Gabrieli says. “Reading is a complicated skill, so there could be a number of different factors that would make you do better or do worse. It could be that those factors are a little bit different in children with more enriched or less enriched environments.”

The researchers are hoping to identify more precisely the factors related to socioeconomic status, other environmental factors, or genetic components that could predict which types of reading interventions will be successful for individual students.

“In medicine, people call it personalized medicine: this idea that some people will really benefit from one intervention and not so much from another,” Gabrieli says. “We’re interested in understanding the match between the student and the kind of educational support that would be helpful for that particular student.”

The research was funded by the Ellison Medical Foundation, the Halis Family Foundation, Lindamood-Bell Learning Processes, and the National Institutes of Health.

Anne Trafton | MIT News Office